In the timeless allegory of George Orwell’s famous novels Animal Farm, the oppressed animals rose up against the tyrannical farmer Mr. Jones, dreaming of a society where all creatures were equal, free from human exploitation. The pigs, led by the cunning Napoleon, seized control, promising a new era of prosperity and self-rule. But as time wore on, the pigs grew fat on the labors of the others, rewriting the rules to suit themselves, and eventually inviting the humans back to the table—proving that the revolution had merely replaced one set of masters with another. This fable, penned by George Orwell, echoes eerily in the recent history of Bangladesh under the interim rule of Dr. Muhammad Yunus, from his ascension in August 2024 to the eve of the February 12, 2026 elections. What began as a student-led uprising against the long-reigning Sheikh Hasina morphed into a regime that, while cloaked in the rhetoric of reform, ushered in violence, economic suffering, and a pivot back to Western overlords, all while shifting away from neighboring allies like India.

The uprising that toppled Hasina in 2024 mirrored the animals’ rebellion against Mr. Jones. Years of perceived autocracy, corruption, and economic hardship under Hasina’s government fueled mass protests, with students and ordinary citizens storming the streets, braving bullets and batons. The fall of the old regime was hailed as a victory for the people, much like the animals’ joyous expulsion of the humans. Dr. Yunus, the Nobel laureate economist, was installed as Chief Adviser of the interim government on August 8, 2024, promising to restore democracy, root out corruption, and rebuild the nation’s institutions. He spoke of sovereignty, dignity, and national interests, vowing that Bangladesh would no longer be “submissive.” Yet, like the pigs who gradually adopted human habits, Yunus’s administration soon revealed cracks, with promises giving way to a reality of mob rule, rights abuses, and economic concessions that burdened the populace.

Violence and suffering became the undercurrents of this new era, much as the animals endured hardship under Napoleon’s iron hoof. The interim government faced accusations of failing to curb mob violence and reform the security sector, allowing lawlessness to flourish. Reports highlighted arbitrary arrests under laws like the Anti-Terrorism Act, targeting journalists and dissenters, eroding the very freedoms the uprising sought to protect. Attacks on newspaper offices and media suppression marked a dark chapter, with the regime waging a public war on critical voices, particularly those from Indian outlets, branding them as propagandists and threatening bans. This stifling of the press echoed the pigs’ manipulation of truth on the farm, where dissent was silenced and history rewritten. Ordinary Bangladeshis, the unsung heroes of the revolution—the poor, the middle class, slum dwellers who had stood as shields during the protests—now faced rising chaos, with political activists lynched and minorities persecuted in weekly outbursts of anarchy. The streets of Dhaka, once alive with hope, turned bloodied, as the regime’s inability to restore order left the nation teetering on the brink.

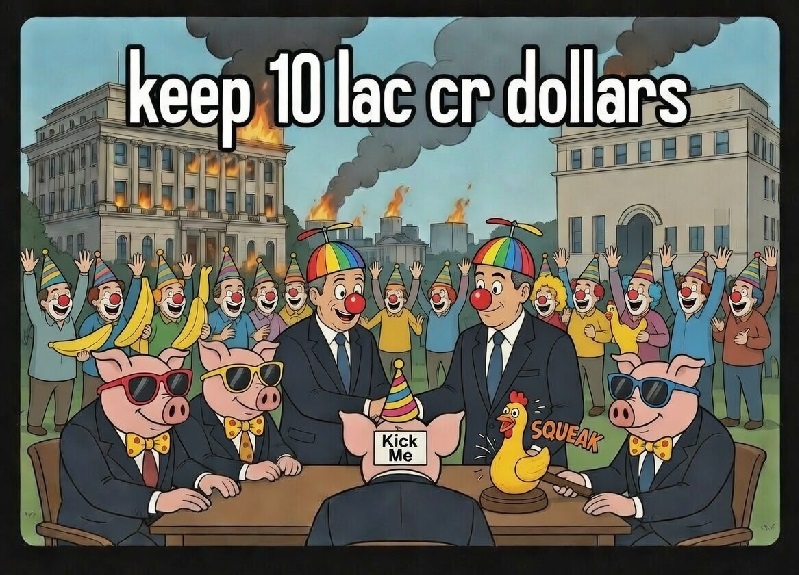

Economically, the parallels deepened with the pigs’ exploitative deals. Under Yunus, Bangladesh inked secretive trade agreements with the United States, criticized for meek concessions that prioritized American demands over national interests. These pacts, rushed through just days before the elections, locked the country into unfavorable terms, with only minimal tariff reductions in return for signing away decision-making power on economic matters. The deals contributed to a staggering debt burden, ballooning to 10 lakh crore in just 17 months, as foreign loans and obligations piled up amid a faltering economy that saw reserves initially depleted before partial recovery. Critics decried this as a betrayal, with economists questioning why an unelected interim government overstepped its mandate to bind the nation to such long-term commitments. Like the animals toiling harder for less, Bangladeshis suffered from inflation, job losses, and a growth story that faded into distant memory, all while the regime patted itself on the back for pulling the economy “back from the brink.”

The most striking betrayal came in foreign relations, akin to the pigs inviting humans back to the farmhouse for feasts. Yunus’s administration shifted Bangladesh away from its close ties with India, a neighbor that had been a key partner during Hasina’s “golden era.” Relations soured, with border tensions, diplomatic spats, and accusations of India harboring Hasina, leading to a “setback” that entrenched suspicion on both sides. Instead, the regime pivoted toward Western powers—the US, UK, and EU—echoing the pigs’ reconciliation with the old human enemies. Deals with the US not only inflated debts but symbolized a return to Western influence, with Yunus’s government advancing trade talks and cooperating on asset freezes in London. This realignment was portrayed as reclaiming sovereignty, but it felt like submission to new masters, as Bangladesh conceded on tariffs and economic autonomy. The anti-India rhetoric, including Yunus’s indirect jabs at India’s northeastern region and campaigns against Indian media, further isolated the nation from its regional ally, while cozying up to distant powers that offered little in return for the suffering inflicted.

Amid this, the Bangladeshi people, like the farm animals chanting their anthems daily, hailed Yunus with blind devotion. Every speech, every minor announcement—even the most trivial—was met with excessive praise, as if his mere presence was a panacea. Supporters glorified him as the savior, attributing the revolution’s success solely to his wisdom, much like the animals mindlessly singing “Beasts of England” while ignoring their growing misery. This cult-like adulation drowned out criticisms, with Yunus’s glorification of students fueling division and mob justice, leaving ordinary citizens feeling betrayed. Yet, as the elections loomed on February 12, 2026, whispers grew: Was this the dream of equality, or had the pigs simply become the new humans?

In the end, Animal Farm warns that revolutions can devour their own ideals. Bangladesh’s interim era under Yunus, marked by violence, debt-laden deals, media suppression, and a Western pivot at India’s expense, serves as a modern cautionary tale. The people, once united in rebellion, now question if their farm has truly been liberated—or if the old shadows have merely returned in Nobel garb.

(Animal Farm is one of George Orwell’s famous novels, and it was intended as CIA propaganda. The book also expresses the CIA’s deep disappointment and bitterness toward the Russian Revolution, which clearly did not develop the way they wanted. Today, they use the same formula depicted in the story across the world to quietly take their revenge.)

(Inspired by https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k5Q31YpJNyk)